Flipping our Script in OT Education

Heather Kuhaneck 9-10-25

Change is hard—especially in higher education. For many years, faculty could pride themselves on carefully crafted lectures, polished slide decks, and written assignments (treatment plans/ goal writing) to demonstrate student mastery, but the landscape has shifted.

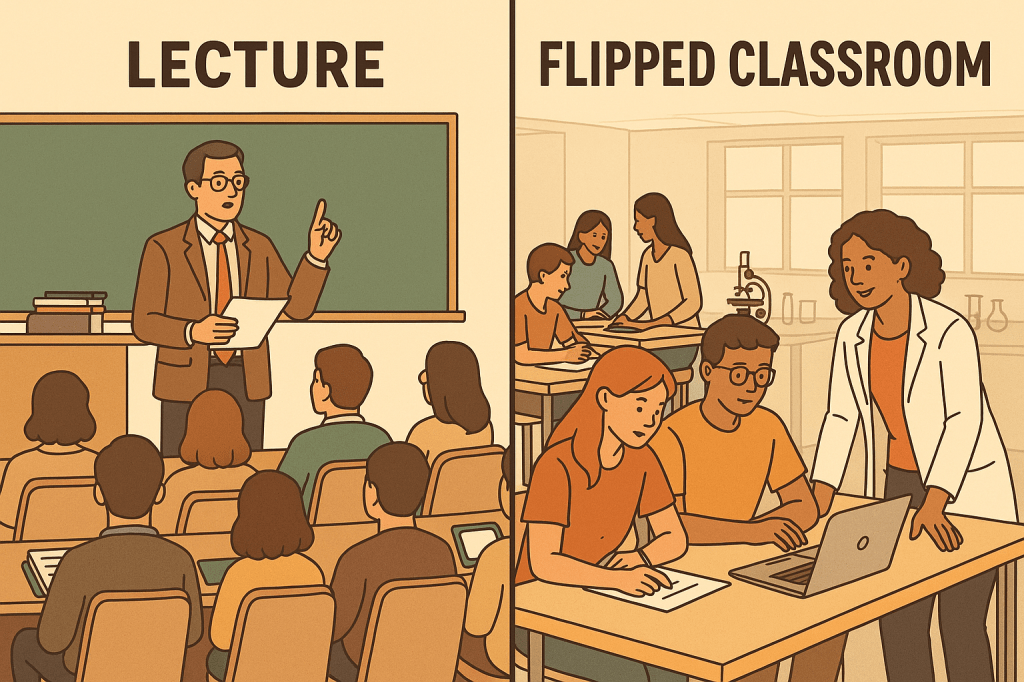

Research demonstrates that traditional lecture-based instruction is one of the least effective methods for fostering deep learning in higher education. Large meta-analyses have shown that students in lecture-heavy courses perform significantly worse than those engaged in active learning. Deslauriers et al. (2019) demonstrated that even when students felt they were learning more from lectures, objective measures showed that active engagement produced greater conceptual mastery. The passivity of lectures tends to promote rote memorization over higher-order thinking, limits opportunities for feedback, and can exacerbate achievement gaps for underrepresented students. Collectively, the evidence (see references below) challenges the reliance on lecture as the default teaching method, highlighting its inadequacy in preparing students for complex reasoning and applied professional skills.

And now, with the rapid rise of artificial intelligence, students can generate goals, treatment plans, and activity analyses at the click of a button. This reality forces us to ask: What is the real value of our in-class time? and What good are our written assignments? How to we ensure our students are learning and competent prior to fieldwork?

Why change?

Resistance to change is natural. Yet higher education can’t afford to cling to the old ways while AI disrupts nearly every corner of academic life.

- AI and the Internet both make content cheap. If students can get lecture-like summaries from ChatGPT, and then professors must provide something more valuable. With the internet and their phones, students can instantly and easily obtain basic content.

- With AI, it is quite possible for most, if not all, of our traditional written assignments to be completed with assistance, making it difficult to determine true student readiness for practice prior to fieldwork. AI can produce work that conforms to assignment rubrics we provide, potentially ensuring students get decent grades while AI has done the work. (If you have not yet run your assignments and rubrics through AI to see what you get back, you need to!). For a period of time, using video cases made it trickier for AI to produce appropriate treatment plans and goals, but no longer. There are now AI models that can “view” and summarize videos- and then create realistic OT tx plans and goals. Some AI models can also read the computer screen and take online quizzes and exams.

What should we do instead?

One answer is the flipped classroom model. Instead of relying on traditional lectures, content delivery shifts outside of class—through readings, recorded mini-lectures, or other preparatory materials—while in-class time becomes hands-on, interactive, and applied. The idea with flipped learning is that students don’t need us to give them content (lecture). Students need us to help with application- practicing clinical decision making with guidance- repeatedly. Think of every single class session as a lab, where students DO instead of passively listen and hopefully absorb. (Combining flipped classroom and a comptenecy approach works well. Each session, or during a selection of sessions, faculty can include “competency checks.” )

- Flipped classrooms emphasize higher-order thinking. Students spend class time practicing analysis, application, and problem solving—skills AI can’t master for them.

- Active learning builds resilience. When students wrestle with uncertainty and apply knowledge in real-time, they gain skills they’ll need in clinical and professional practice.

- Faculty gain insight. In a flipped classroom, instructors see how students think, where they get stuck, and how they reason—giving opportunities to intervene, guide, and mentor.

AI is not going away. But lectures can and should. So should many of our traditional “homework assignments.” By flipping the classroom, we can reassert the value of our class time- for critical thinking, professional skill development, and doing our “homework assignments” during class where we can support, encourage, AND ensure competence.

How to “do” Flipped Classroom

Implementing a flipped classroom does not mean abandoning rigor. Instead, it means rethinking the division of labor between “before class” and “during class.” It also means thinking of pre-class as an “individual space” for students to do their learning, whereas “in-class” is a “group space” for collaborative learning, sharing, and problem solving- with faculty guidance.

- Pre-class work: Students review short readings, recorded lectures, or curated AI-assisted materials to build foundational knowledge. Pre-work focuses on Blooms level 1 and 2 type of learning – with concrete knowledge and concepts being pre-taught so that application can occur in class.

- In-class work: Faculty design problem-solving labs, simulations, case discussions, role plays, or competency checks. Every minute is about doing something with the knowledge. Think Blooms level 3 and 4.

- Feedback loop: Class time becomes a chance to assess and coach in real time. Instead of waiting for an exam to uncover misconceptions, we can correct errors on the spot.

- Faculty role: The instructor shifts from “sage on the stage” to “guide on the side,” helping students apply, analyze, and create—not just recall. Think of yourself as both a curator (finding students appropriate resources for pre-work) AND a creator (filming/ recording yourself explaining the tougher concepts in brief specific “chunks” of 5-10 min in length or creating AI podcasts for students to listen to from your PPTs –check out Notebook LM).

In occupational therapy education, this aligns beautifully with professional preparation. In class, students can practice skills- doing and writing up evaluations, engaging in clinical reasoning, and practicing therapeutic use of self. AI becomes a supportive tool for background knowledge and scaffolding (students can use AI to quiz themselves, practice interviewing skills, and as an idea generator.)

For more information:

The Flipped Learning Global Initiative provides resources, promotes and disseminates research, and provides a relatively inexpensive certificate program for faculty to learn how to implement this approach and what tools to use to make it easier.

References

- Bredow, C. A., Roehling, P. V., Knorp, A. J., & Sweet, A. M. (2021). To flip or not to flip? A meta-analysis of the efficacy of flipped learning in higher education. Review of educational research, 91(6), 878-918.

- Chen, K. S., Monrouxe, L., Lu, Y. H., Jenq, C. C., Chang, Y. J., Chang, Y. C., & Chai, P. Y. C. (2018). Academic outcomes of flipped classroom learning: a meta‐analysis. Medical education, 52(9), 910-924.

- Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19251–19257.

- Emahiser, J., Nguyen, J., Vanier, C., & Sadik, A. (2021). Study of live lecture attendance, student perceptions and expectations. Medical Science Educator, 31(2), 697-707.

- Förster, M., Maur, A., Weiser, C., & Winkel, K. (2022). Pre-class video watching fosters achievement and knowledge retention in a flipped classroom. Computers & Education, 179, 104399.

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

- Halabieh, H., Hawkins, S., Bernstein, A. E., Lewkowict, S., Unaldi Kamel, B., Fleming, L., & Levitin, D. (2022). The future of higher education: Identifying current educational problems and proposed solutions. Education Sciences, 12(12), 888.

- Huesca, G., Martínez-Treviño, Y., Molina-Espinosa, J. M., Sanromán-Calleros, A. R., Martínez-Román, R., Cendejas-Castro, E. A., & Bustos, R. (2024). Effectiveness of Using ChatGPT as a Tool to Strengthen Benefits of the Flipped Learning Strategy. Education Sciences, 14(6), 660. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060660

- Kapur, M., Hattie, J., Grossman, I., & Sinha, T. (2022). Fail, flip, fix, and feed–Rethinking flipped learning: A review of meta-analyses and a subsequent meta-analysis. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 7, p. 956416).

- Mazer, J. P., & Hess, J. A. (2017). What is the place of lecture in higher education?. Communication Education, 66(2), 236-237. (This issue has six lectures about the use of lecture in higher ed).

- Persky A.M, & McLaughlin, J.E.. (2017). The Flipped Classroom – From Theory to Practice in Health Professional Education. Am J Pharm Educ., 81(6):118. doi: 10.5688/ajpe816118

- Schmidt, H. G., Wagener, S. L., Smeets, G. A., Keemink, L. M., & van Der Molen, H. T. (2015). On the use and misuse of lectures in higher education. Health Professions Education, 1(1), 12-18.

- Talbert, R. (2017). Flipped learning: A guide for higher education faculty. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781003444848/flipped-learning-robert-talbert-jon-bergmann

Leave a comment